“Once upon a time…”

With those immortal words, Russell T. Davies introduces us to his second era as head writer of Doctor Who. As someone who wrote her master’s thesis on the relationship between Doctor Who and fairy tales, of course I was delighted, just as I was with the invocation of the Brothers Grimm in “Heaven Sent.” It felt like a nod to me; to the kind of Doctor Who that I prefer. But it’s more than the smug feeling of being validated. (As “The Giggle” will show, the need to be proven right is not humanity’s best quality.) It’s all the things that those timeless words imply. The comfort of a storytelling tradition, of being in a safe pair of hands, of sitting back in anticipation of being told a good yarn. There’s a line in Inside Llewyn Davis that goes “if it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.” Fairy tales are like that, and so is Doctor Who. Like the TARDIS it’s both old and new. When you step inside you both know and don’t know what to expect. Paradoxical.

Look, it’s obvious that I didn’t have much to say about the Chris Chibnall era. If you love the Thirteenth Doctor and/or Chibnall’s tenure, no offense is meant. I certainly mean no disrespect to Jodie Whittaker, who did her best with what she was given. Every era of Doctor Who is for someone, which means that each is equally and emphatically not for someone else. The most wonderful thing about the Doctor is that they contain such multitudes. I am going to resist the temptation to give Chibnall a hard time throughout Davies’ second run. But I’m afraid that I have a few frustrations to get out of my system, and so there will probably be a disproportionate amount of comparison-contrast in this post.

And boy howdy, the contrast feels stark. Did every single thing in these three specials work for me? Of course not. Davies has always been a bombastic, broad, and at times messy writer. And that’s good — he makes you feel things. But within the high emotion and spectacle, there’s a core simplicity. You know who his characters are. One season and a few specials with Donna gave her a clarity and a strength that we never got in three seasons and more with Yaz. You know the purpose of each story, what it’s doing to further the overall theme and character development. His episodes are about something coherent: the fraught relationship between appearance and identity; the Doctor and Donna’s relationship; our violent and tribalist culture war. I’m not saying there are no Chibnall era episodes that achieve that kind of dramatic unity, but by the end of each season I always felt lost in the weeds of technobabble exposition, incoherent plot mechanics, and general purposelessness. Though Steven Moffat could get carried away with the cleverness of his plots, they also always stemmed from and informed character. It’s not easy to avoid the impulse for more. The Reality Bomb was no more plausible than the Flux, but Davies always brought things back to the characters. The stakes are in what happens to be the people, never what happens to the universe. Indeed, in a kind of alchemical process, what happens to the universe at the end of each Davies or Moffat season merely reflects and reiterates the transformation within. Davies spoke of needing to have “words with [himself]” over “Wild Blue Yonder”: “Just stay true to the idea […] Stick to the idea.” While Davies is not a simplistic writer, there is a simplicity to his ideas that gives them strength. The result is a welcome synergy of theme and content across the three specials.

But rather than wander all over the place aimlessly, let’s look at each episode in turn.

The Star Beast

“The Star Beast” is an excellent case study in this synergy. The core theme of the tenuous relationship between outward appearance and inner reality is mirrored in everything in “The Star Beast” from Rose’s gender identity to Donna’s sneaking sense that her outwardly normal and happy life masks an inner emptiness, and of course the wonderful Beep the Meep’s cute and cuddly exterior masks the true megalomaniac within. The Fourteenth Doctor himself is questioning this relationship as well: An old face has returned. Surely that must mean something. Sometimes outward appearances can distract or mislead us; at other times they point to a deeper truth.

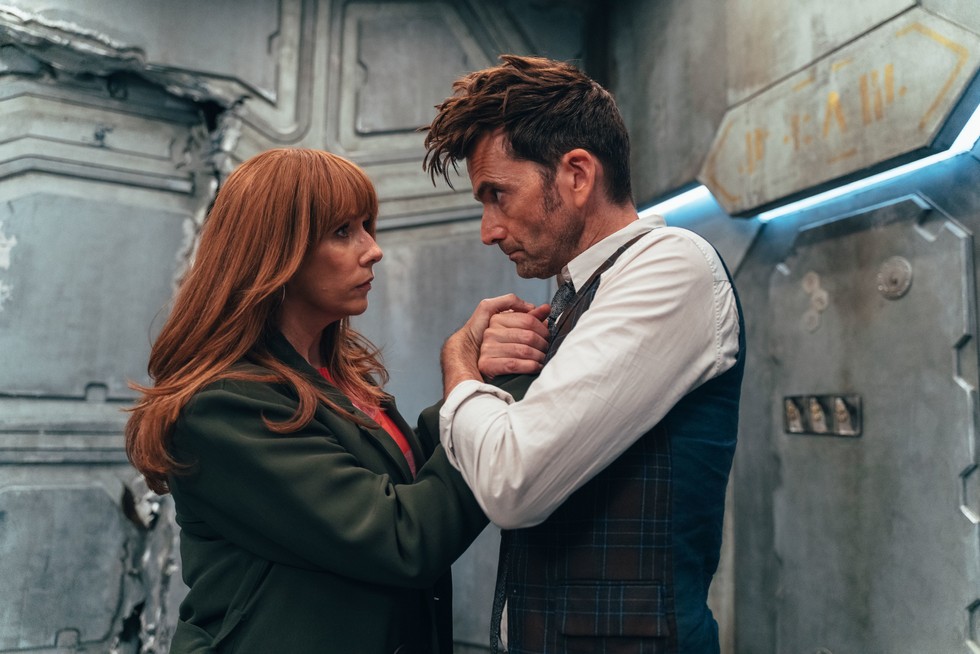

Thematic neatness aside, “The Star Beast” is an efficient and brisk reintroduction to the world. The slightly awkward direct-to-camera prologue, recapping the events of Series 4, makes me wonder what a new viewer would make of all this. The timing of the move to Disney+ before resolving the dangling DoctorDonna threads is slightly odd, but Donna’s missing memories and Rose Temple-Noble as the young, curious, starry eyed companion a la Rose Tyler make for a smooth enough reentry. More than anything, what stands out are David Tennant and Catherine Tate’s performances and insane chemistry. Their genuine connection, evident in both life and art, lights up the screen. They draw emotional depths and comedic heights from each other in a really unique way.

Tennant has talked about this Doctor being more human than the ones before (which will pay off in “The Giggle”). The Tenth Doctor was fairly human anyway, but I agree that there’s a further modulation in the Fourteenth. He’s no less melancholy than the Tenth but definitely less troubled and angry. It’s actually a lovely, emotive performance, and it’s kind of great to see Tennant’s take on the Doctor unburdened by the tragic flaws Davies gave him the first time. I’ve always seen Ten as the tragic hero of the New Who Doctors – he begins his tenure by deposing a world leader, climaxes as the Time Lord Victorious, and endures an anguished and ambivalent regeneration (“I could do so much more,” “I don’t want to go,” etc.). It’s a complicated and rich character arc but not really a happy one. But much has been, if not healed, at least confronted since then.

This is why coming back to Donna makes sense. Naturally the thought of coming back to what I thought was a pretty satisfying end for Donna (on a narrative level if not a personal one) made me a little nervous. I’ve never been as angry at Davies for Donna’s ending as some others have. I enjoy a tragic ending now and then. But if Donna represents a key piece of unfinished business for Tenth Doctor, then he had to come back to find resolution. Rachel Talalay’s excellent direction of the climactic scene mirrors the Doctor and Wilf in “The End of Time” – separated by glass, powerless to stop the inevitable. The Doctor has to allow her the thing he denied her in “Journey’s End” – her choice. “Best fifty-five seconds of my life,” she declares, joyfully choosing to sacrifice herself for the world. Naturally, she is eucatastrophically saved by Rose, who siphons off the extra Meta Crisis energy and shows the DoctorDonna a third way between the binaries of death and Time Lord immortality (what Tolkien would call “endless serial living”), Rose and Donna embrace their normal human lives and show the Doctor how to “let go.” I’m not sure if Rose is correct that all “male-presenting” Doctors need to learn this lesson, but Tennant’s Doctors certainly do.

“The Star Beast” ends on a giddy high, with the Doctor and Donna squeeing over the new TARDIS, the Doctor running laps around its vast circular ramps, and Catherine Tate performing what might be the funniest bit of physical comedy in the series so far.

I want to note my friend Tom Hillman’s wonderfully observed mention that the scene of the Doctor and friends escaping the Zogroth by crawling from one attic to the next is of course a nod to C.S. Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew. My favorite recent homage to The Magician’s Nephew comes from Susanna Clarke’s brilliant Piranesi, and we know from that novel that Clarke is a fan, or at least has working knowledge of Doctor Who (she references “Blink” and Steven Moffat by name). So I will take this as a hint from Russell to me personally that my fantasy of a Susanna Clarke-penned episode will come true in 2024. She’s writing again. She’d be perfect.

Wild Blue Yonder

There is a slight breakdown between theme and content at the end of “Wild Blue Yonder” that holds me back from loving it unreservedly, and it’s one of Davies’ few major missteps in these specials. The episode went to some fairly dark places and flirted with pushing the Doctor and Donna’s relationship to a breaking point in their initial anger and blaming each other for their predicament. It’s very much in the vein of “Midnight,” “Heaven Sent,” “Listen” – episodes that push the Doctor to his limit. It’s no mistake that all of these examples, “Wild Blue Yonder” included, take the Doctor to the limit of his knowledge of the universe – at the end of known time and/or space. Davies’ natural salesmanship undermines him a bit when he suggests that the Doctor has never had an adventure like this before, but nevertheless it’s a type of Who episode that I generally love.

Clearly this is what the episode wants to be about: The Doctor and Donna have jumped back into the TARDIS as if no time has passed at all, when lurking underneath is the reality that their relationship ended in a kind of betrayal, with the Doctor wiping her memories despite Donna begging him to stop. So here at the edge of everything, they’re confronted with the most terrifying monsters of all – themselves and each other. After all this time apart, Donna deprived of her memories and the Doctor having lived through several more million years of loss and trauma, how well do they even really know each other or themselves? But it’s more than the old “humans are the real monsters” theme, a la “Midnight.” Instead I’m reminded of Tom Bombadil’s question, “Tell me, who are you alone, yourself and nameless?” Deprived of her history, Donna describes feeling adrift. Her existential crisis finds its mirror in the formless, chaotic, ahistorical No Things who drift about the void of space looking to approximate a superficial, outward resemblance to humanity.

“Listen” suggested that the Doctor’s endless quest against the monsters is due to a plain old fear of the dark. “Midnight” depicted the Doctor as powerless when deprived of his ship, his friends, and most crucially his voice. I can feel “Wild Blue Yonder” wanting to finish with a similarly core conclusion about who the Doctor is, whether or not the revelation is a happy one. Ultimately, the scariest thing is that the Doctor doesn’t recognize Donna. He chooses the copy; and he only realizes his mistake, not by anything in her nature or character, but by her ever-so-slightly-too-long wrist. It’s a disappointingly technical solution to what is an otherwise emotional story. Maybe, as Donna suggests in the following episode, the Doctor is just tired, but if I was her, I would be a little disturbed by that. Davies writes fabulous ambivalent endings. It’s a shame we had to go straight into the climactic third episode, when the ending of episode 2 could have used a bit more time to sit with the consequences of this error. I could imagine a more fulfilling version of this story that reaffirms their friendship when the Doctor realizes the copy’s sense of humor is not quite right. Equally, a more challenging version would culminate in Donna’s anger or hurt at the Doctor’s mistake. Instead, we kind of rush past it, merely relieved to have narrowly escaped. Perhaps they’re afraid to look too closely at the implications. It reminds me of the Doctor’s words at the end of another episode in this mode, “The Satan Pit”: “I think we beat it. That’s good enough for me.” Best not to think about it too much.

This might be one of those stories that grows on me, and I may change my mind entirely after I read some other takes. Critiques of the ending aside, “Wild Blue Yonder” is one of the weirder episodes in the show’s history and an absolute hoot. In fact, all three specials looked fabulous, from the blessedly practical Meep to the disturbingly cartoonish No Things to the demented glee of the Toymaker. The Disney money has not come at the cost of the show’s inherent camp. There’s a humor to all three that feels welcome and invigorating (and if the upcoming Christmas special’s goblins are any indication, it’s not going anywhere for the time being). Given the pace of the first and third episodes, it’s a welcome change to spend an hour in the middle simply indulging Tennant and Tate’s talent. I could spend this entire post gushing about their performances. What a joy to watch them be heroic and evil, smirking and sincere, dragging along giant prosthetic arms with complete commitment.

There’s another talent of Davies’: iconic names and phrases. Bad Wolf. The Nightmare Child. “There’s something on your back.” Yes, he could create a euphonious or memorable alien name when he had to (see Raxacoricofallapatorius or the Ood). But mostly he plants these ideas in your mind with mundane words. It’s no wonder Moffat latched onto the Moment as the central mythic concept in “The Day of the Doctor.” So, welcome to the club, “My arms are too long.” Like “Don’t blink” or “Donna Noble has left the Library,” I can totally see using this to creep someone out. (Moffat is good at this, too.)

There’s much to love here, even if I wanted to sit with the consequences of the ending a little bit longer. Perhaps this otherwise excellent episode is a slight victim of the brevity of the Fourteenth Doctor’s run.

The Giggle

Where to start with this one? What a wild ride. I’m hugely impressed by the deftness of Davies’ weaving the disparate themes together into a coherent whole. We get a story about the invention of the television which implicates the role of media in the hysterical and reactionary frenzy which characterizes the 2020s. Not that TV invented anger, lies, or self-righteousness, the Doctor hastens to add. “Using your intelligence to be stupid, and hating each other, you never needed any help with that.” And yet, the creation of mass media carries with it an original sin from its inception.

As Davies said, the presence of a puppet implies a puppet master. So the historical accident of Stooky Bill inevitably pointed Davies to the Toymaker. He joins these themes (games, toys, and play; hateful polarization; and the influence of TV) through the idea of “winning.” When all that matters is winning, life becomes a game of one upmanship. Right and wrong don’t matter when all one cares about is being proved “right.” “Your good and your bad are nothing to me,” says the Toymaker. “All that matters is to win and to lose.”** And this is the irony of tribalism. For all that it claims to care about truth and morality, in the end all that matters is the game itself, and being on the winning team.

Is it subtle? Not really. But it’s smart and insightful. Cheekily, Doctor Who escapes Davies’ implication of visual media. Not because the Doctor is above self-righteousness, and he admits it in this episode (“I’m always so certain.”). Rather, it’s the broadened perspective afforded by the TARDIS, our stand in for the imagination. Davies is really embracing the fantastical and imaginative aspects of Who, and I’m loving it. Though I have argued that Davies’ original era did its own spin on the fairy tale genre, it was equally grounded in the dramatic soap opera. These specials almost feel like a blend of Davies’ grounded approach with Steven Moffat’s more overtly whimsical tone.

On that note, I’m also enjoying watching Davies respond to Moffat who was responding to Davies. To go back to the theme of games, there was always a sense of (friendly) competition between them. Each of them trying to “beat” the other often led to creative highs. While I love both eras (and I think they truly love and respect each other), the Toymaker’s puppet show feels like a direct response to Moffat’s implicit critiques of Davies’ storytelling tendencies, particularly in “The Day of the Doctor.” While “Day” essentially undoes the destruction of Gallifrey (while respecting its function in the narrative and character development), Davies’ pokes at Moffat’s tendency toward transhumanism in the pseudo-happy endings of each of his companions. The Toymaker shows Donna how each companion died with increasingly hollow protestations from the Doctor: Amy died of “old age;” Clara (“killed by a bird!”) “survives in her last second of life”; Bill’s consciousness survives. Neil Patrick Harris’s increasingly sarcastic “well that’s all right then!” after each equivocation was perfect and made this Moffat fan laugh out loud. (The Chibnall companions, lacking satisfying or dramatic endings, are politely avoided. A few references to the Flux and the Timeless Child aside, these episodes engage much more directly with the former Davies and Moffat eras than they ever do with Chibnall. Which makes sense. I’m still not really sure what the Flux was.)

But neither Davies or Moffat take cheap shots for the sake of it. They both know how to blow up the narrative when it suits their larger purpose. Davies had to destroy Gallifrey to kickstart the new series. Moffat had to restore it in order to move the Doctor into the next phase. Ten years on, Davies is in much the same position. Tasked with reintroducing Doctor Who once again, no wonder he had the tension between rules and play on the brain. Every game lives in this tension. Without a playful sense of fun, games become mere exercises in pedantry. But without rules, a fun game devolves into chaos. We all know it is infuriating to play a game with someone who changes the rules arbitrarily. The rules of “canon” (to invoke that dangerous and probably inappropriate word) are something like this. Should we break the rules? Well, the question is: Does it make the story better? Tolkien, maybe the best retconner who ever lived, found a way to keep the original story of Bilbo’s finding of the Ring while completely rewriting the chapter to fit The Lord of the Rings. Rather than discard the old story, he devised a way in which both versions could be true.

I’m not sure Davies is quite that good, but he’s pretty close. He puts it all together – the Time War, the loss of all his companions, the burden of long years, and yes, even the Flux – and concludes that it’s just too much. How can any character, even the Doctor, bear the weight of all that history and mythology? And so, with the Doctor superstitiously throwing salt everywhere and the Toymaker turning people into balloons with the power of thought, Davies takes advantage of the loosening of the rules by literally splitting the show in two. It’s a paradox: the Doctor stays home and retires while the Doctor flies off to start a new adventure all over again. It’s slightly ironic, given Davies’ critique of Moffat just a few minutes ago. You can imagine the scene:

FAN: Russell, you made the Fourteenth Doctor retire to Donna’s garden.

RTD: But the Fifteenth Doctor flew off in the TARDIS!

TOYMAKER: Well that’s all right then!

Hannah Long suggests that Bi-generation is a direct response to Chibnall’s Timeless Child mythology: “Chibnall broke the canon of the show in such a way that it feels like it’s retiring its old self for good.” That may be the case, although this isn’t the first time we’ve had this kind of reset. The Time War served as a similar blank slate. The Cracks in Time essentially ate all the Davies era continuity so that Moffat could start fresh. The Twelfth Doctor was pointedly said to have forgotten Madame de Pompadour, or so he claims. It’s not even the first time Tennant’s Doctor has left a comparatively “human” version of himself behind with a companion. (His Doctor is just lousy with doubles, isn’t he? Not that I’m complaining.) How far reaching are the implications of “The Giggle” remain to be seen in the new season. But I’m willing to buy that this represents a fundamental shift in Who, even if we’re not quite sure how yet. Maybe it’s a shift in tone, or a break in continuity. Maybe it’s just setting up Tennant and Tate for a spinoff. Who knows? (On that note, I do love the notion that the Fourteenth Doctor ends up as the Curator.)

Fans who found the Tenth Doctor’s petulant final moments disrespectful to Moffat and Matt Smith will probably hate this. And while I take their point, I think that reaction misunderstands Davies’ intent. Like Donna, Davies knows that people are capable of believing two completely opposite things at the same time. You can feel excited for the new Doctor while mourning the old one. Having been a workaholic who left Doctor Who and settled down for a comparatively quiet period of domesticity, Davies surely knows what it feels like to wish you could clone yourself. Half of you wants nothing more than to retire to a quiet garden with friends and family. The other craves mad adventures in time and space. Whereas Moffat poked fun at Ten’s final words (“he always says that”), Davies fulfilled them. With the Tenth Doctor’s face returned (a bit older and wiser), having redeemed himself by restoring his best friend, he accepts that “it’s time.” (Even though they’re not his final words, “allons-y” is perfect.) He surrenders himself and accepts his loss. He’s finally at peace.

It’s always in these moments of quiet surrender, poised between hope and despair, that we get the best eucatastrophes in fairy stories. The villain betrays himself and does good that he does not intend. Having suspended the normal rules of the universe, the Toymaker allows the Doctor’s regeneration to be governed by a different set of rules – those of story and play. An unexpected and unearned grace is given to the hero. The Doctor does a thing which is only possible in myth. The narrative doesn’t so much break as separate, like drops of liquid mercury. Having played by the rules of the Toymaker’s game and accepted the outcome (in contrast to the earlier Time Lord Victorious who declared, “The Laws of Time are mine – and they will obey me!”) the Doctor unexpectedly levels up and gains an advantage. This time, there’s two of him. The two Doctors team up and beat the Toymaker at his own game. (Though their victory is almost undone by Ncuti Gatwa’s capricious Fifteenth Doctor who momentarily loses himself in the game and forgets whose side he’s on. Can’t wait to see more of him.) Having won the game, each Doctor gets a prize: a TARDIS and the life of his choosing. In a sense, Davies gifts Tennant’s Doctor what he always wanted fifteen years later: He doesn’t have to go. He gets to stay.

Cruel though the Toymaker is, Bi-generation is a fitting use of his powers. The Doctor appeals to an underlying potential for good: “You can turn bullets into flowers.” The Toymaker may choose to use his powers for evil, but his powers are not necessarily evil by nature. After he’s defeated and bound in salt, the Fifteenth Doctor speaks of them still being in a “state of play.” “What if…” he says right before duplicating the TARDIS, as though about to initiate a game of pretend. Yes, TV can be used for manipulation and provocation. But it’s also a storytelling medium, which means that it has the potential for creativity, imagination, and empathy. This playfulness has always informed Davies’ approach to the series. “Doomsday” is largely the fulfillment of childhood dreams of the Daleks fighting the Cybermen. Like all great writers of speculative fiction, Davies sits down to write each episode, considers the range of toys at his disposal, and thinks to himself, “What if…”

So the 60th Anniversary ends with a kind of wish-fulfillment. I very much doubt it’s a permanent fix for the Doctor’s wounds. Nothing in this life completely insulates us from loss and pain. If I’m troubled by anything, it’s the memory of Frodo’s words to Sam: “You cannot always be torn in two.” The Fourteenth Doctor still has his TARDIS. He’s already sneaking off to Mars with Rose and building force fields around the local moles. But regardless of how quickly he becomes restless or whether or not we see Tennant’s Doctor(s) again, the episode ends in a warm affirmation of what is worth fighting for. Family. Peace. Home. With the knowledge that the Doctor is out there defending the Earth and exploring the universe, he’s no longer alone. He Doctor can let go and rest. At least for a bit. Donna echoes the Doctor’s words to Rose in “Doomsday” when she describes the adventure of living life day after day – “The one adventure you’ve never had.” It’s a conscious echo of the ending of Peter Pan, when Peter observes the Lost Boys being adopted into the Darling family: “There could not have been a lovelier sight; but there was none to see it except a little boy who was staring in at the window. He had had ecstasies innumerable that other children can never know; but he was looking through the window at the one joy from which he must be for ever barred.” The Fifteenth Doctor gets one kind of joy; the Fourteenth Doctor another.

Donna said that “games don’t have a memory” – “the dice don’t know what the dice did last time.” The laws of story dictate that Doctor Who must regenerate and carry on. Ncuti Gatwa has the fresh face of every new Doctor. The show must shed its old persona and create something new if it’s to survive. It must always in a sense forget what came before if it’s to start over. But with the strangely human Fourteenth Doctor, Davies gestures at the more fundamental laws of human nature. The need for memory, healing, and stability. Our toxic tendency to just power through grief and pain, always moving on, afraid to look back. It’s a poignant statement from Davies who lost his husband prematurely to brain cancer in 2018. In “The Giggle,” the Doctor goes to therapy (albeit slightly out of order). Like G.K. Chesterton, I love a good paradox. In accepting his grief, the Doctor finally exorcizes it. He sees himself, embraces himself, forgives himself… and lets the burden go. Even after all he’s suffered, the Doctor is able to say that he’s “never been so happy.” Only by sitting still with his grief (surrounded by a supportive family in a beautiful garden) can he finally leave it behind and fly off without it, free as a bird. It’s a fitting and moving culmination to the story that Davies initiated back in 2005.

And now Davies gets to initiate a new era. Don’t get me wrong, I love the weepy and sensitive Fourteenth Doctor, but there was something cathartic about Fifteen’s frank, “OK kid, I love you. Get out.” What kind of story will he tell this time? Paradoxical as ever, it appears the Christmas special will feature the Fifteenth Doctor meeting his new companion in a nightclub as well as singing goblins a la Tolkien and George MacDonald. Even more than usual, Doctor Who contains multitudes.

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below or in the Mythgard Institute’s upcoming Doctor Who themed Pub Night: On January 14 at 6:00 PM Eastern Time, Curtis Weyant and I will host an informal and virtual chat about the 60th anniversary specials and the upcoming Christmas special. You can register here. Bring your thoughts, corrections, and (respectful) rants along with you.

**I’m not going to weigh in too much on the racist undertones of the Toymaker. For compelling arguments for and against those (intentional or not) undertones in the original Classic Series story, I recommend googling El Sandifer’s TARDIS Eruditorum essay on “The Celestial Toymaker” and @AMadmanNotABox’s recent Twitter thread. But whether the racism was inherent in the original episodes or entered the conception of the character later on, there’s no doubt that it’s part of the popular idea of the Toymaker now. By having the Toymaker flip between various accents and costumes, Davies lampshades and incorporates this aspect of the character and aligns these problematic characteristics with his villainy. Instead of saying, “The Toymaker is villainous because he’s Chinese,” it’s staying, “The Toymaker is villainous because he play-acts and mocks cultures and identities at a whim.”